Directed by Sam Mendes, Screenplay by William Broyles Jr. Universal Pictures, 2005. Color, 2 hours and 3 minutes.

Directed by Sam Mendes, Screenplay by William Broyles Jr. Universal Pictures, 2005. Color, 2 hours and 3 minutes. Directed by Sam Mendes, Screenplay by William Broyles Jr. Universal Pictures, 2005. Color, 2 hours and 3 minutes.

Directed by Sam Mendes, Screenplay by William Broyles Jr. Universal Pictures, 2005. Color, 2 hours and 3 minutes. Written and Directed by Robert Rodriguez. Columbia Pictures, 1995. Color, 1 hour 44 minutes.

Written and Directed by Robert Rodriguez. Columbia Pictures, 1995. Color, 1 hour 44 minutes. Written and Directed by Troy Duffy. Franchise Pictures, 1999. Color, 1 hour 48 minutes.

Written and Directed by Troy Duffy. Franchise Pictures, 1999. Color, 1 hour 48 minutes.

Written and Directed by Chris J. Ford. Independent, 2008. Color, 1 hour 39 minutes.

Written and Directed by Chris J. Ford. Independent, 2008. Color, 1 hour 39 minutes. Directed by Shawn Levy, Written by Josh Klausner. 20th Century Fox, 2010. Color, 1 hour 28 minutes.

Directed by Shawn Levy, Written by Josh Klausner. 20th Century Fox, 2010. Color, 1 hour 28 minutes.

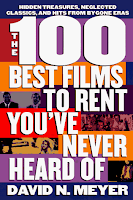

The 100 Best Films to Rent You've Never Heard Of: Hidden Treasures, Neglected Classics, and Hits From By-Gone Eras

Rififi is a low-budget film noir directed by Jules Dassin in 1956. The story follows a group of criminals who decide to break into a jewelry store. Their plan is perfect, and they would have gotten away with it if it were not for the short-sightedness of some of the members of the gang. Dassin did a lot that seems inventive even to a modern audience. The thirty-minute robbery sequence with no dialogue kept a class of twenty-somethings on the edges of their seats. The dialogue in the other three quarters of the movie is in both French and Italian, based on character and situation. Death scenes happening off camera heighten the suspense of the plot. All these combined make Rififi a thrilling noir that has transcended time and language.

I think the most interesting thing I got out of my recent viewing of the film, however, was the attitude towards the women in the movie. In 1949, Simone de Beauvoir wrote The Second Sex, a major work of feminist literature, and not her first. Feminism in France and America would not emerge very strongly until later in the 60’s, but Beauvoir’s writings sparked many feminists to action.(1) Also, the Civil Rights movement was starting to take place right around the time this film was made, and the McCarthy hearings were going on.(2,see page 391) Dassin, born in Connecticut, was himself blacklisted during the McCarthy hearings, causing him to move to France to try and revive his career. Rififi was the first film he made in Europe, writing, directing, and acting in the role of Cesar le Milanais.(3) Dassin was a victim of a world that did not think women, blacks, and communists deserved any rights. It is because of this that I find Dassin’s treatment of women in Rififi so interesting.

In typical film noir movies, there is a femme fatale character who is idealized and sexualized, particularly by soft lighting and mysterious portrayal. Typically the femme fatale is the character that launches the protagonist into the conflict of the film, and usually ends up as the antagonist herself. In this film, however, there is no real femme fatale character. It could be argued that Tony decides to rob the jewelry store because of his rejection by Mado, but Tony’s motivation seems to run deeper than that. Cesar’s need to shower Viviane with gifts is what leads to the gang getting caught, but she is not smart enough or conniving enough to be a classic femme fatale. The only character that seems to fit the previous description would be Tonio, Jo’s son. It may be safe to assume that it is because of Tony’s desire to dote on Tonio, as well as Jo’s need to protect and provide for his family is what drives the two men to perform the heist. Later, the kidnapping of Tonio is what ultimately leads to the death of both Tony and Jo.

Since there is no strong, female character, we see a lot of submissive women in this movie. True, Mario’s wife is sexy and independent, but she will do anything for her man. Jo’s wife is very submissive to him. Mado explains how she needs men to rely on before Tony beats her with his belt. And Viviane sings a song titled “Rififi” in which she says she loves when her man treats her rough. So why, when minorities were just starting to become empowered in the US and France, did Dassin portray so much masochism? I researched feminism in Rififi, but I could not find any reference that explained Dassin’s decisions or his idea in making the film. I would be really curious to know if he supported or opposed this view towards women. Perhaps it was just to convey the story; perhaps it was Dassin subliminally putting in his attitude. I think it is an interesting idea that warrants further exploration.